Output from the VE library concerns the generation of images and sound to form the virtual environment. VE is concerned with the management of this output (e.g. setting up windows, opening channels) and providing a means for applications to provide the actual output data. VE does not include a high-level model for output (e.g. scene graphs), but instead relies on applications to generate the specific calls to do the actual rendering.

All VE programs operate with respect to a physical environment (usually just referred to as the environment). This physical environment consists of computer displays, projection screens, audio speakers, headphones, head-mounted displays, etc. The environment describes:

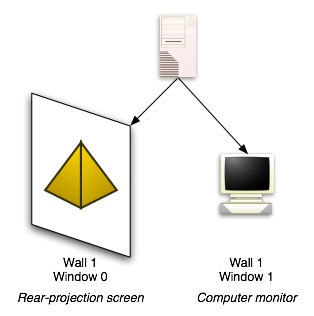

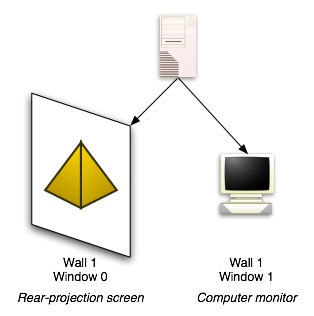

Given that the relation between a physical display and its computer model (i.e. to which host it is connected and how to talk to it) may not be robust, these concepts are broken down into two representations. A physical display is represented in VE by a wall. A wall contains the physical information about a display's size, location and orientation. The computer output that communicates with a display is referred to as a window. The window contains the information about the host to which a display is connected, the specific device or method of access (e.g. an X display) to the output device, where in the output device's framebuffer the image should be displayed, as well as correction parameters to help in fine-tuning and the reduction of distortion.

This model affords a certain flexibility. For example, it is possible for the contents of a wall to be easily displayed on multiple windows. This allows for easy monitoring of an immersive virtual environment by a user outside of that environment.

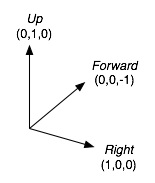

VE has a native or natural mapping onto a Cartesian space.

Even with this "natural" mapping, there are multiple co-ordinate spaces in which a value may be defined. The layout of walls is defined in physical space. This is the co-ordinate space of the physical world in which displays, etc. are located. The precise layout of this space is not important, but following the layout of the native co-ordinate space as closely as possible makes future work simpler.

In simulating a virtual environment, one can imagine the space of the physical environment, at any point in time, is mapped onto a particular space of the virtual environment. In other words, at any point in time, we can define a relation between the co-ordiante system of physical space with that of the virtual world, or virtual space. This relation between physical space and virtual space is called the origin. In effect, it tells us where in virtual space, the physical space is "located".

Imagine a stationary bicycle mounted in front of a projection screen, on which a virtual world is being displayed. As a user pedals, the image on the screen should change as though the user is moving through the virtual environment. However, the user is not physically moving. The effect is as though the physical space itself is moving through the virtual world. Thus the origin is not constant - it changes as the relation between physical space the virtual space changes.

Now imagine that we have the same projection screen but instead of a stationary bicycle, the user is free to walk around. Much as what we see through an outdoor window changes as we move in relation to that window, so should what a user sees on the projection screen change as they move in relation to it. In this case, however, the user is moving with relation to physical space. We define this relation to be the eye and it is the relation between physical space and the personal space of the user, also known as eye space.

Currently, VE only supports the notion of a single "eye". Note that we do not limit ourselves to only supporting cyclops - the "eye" in this case is a virtual construct to identify where the user is. The software can cope with the fact that most people do have two eyes. This does mean that there is a limitation of a single user of the a given VE program.

The origin and eye play different roles. The origin is typically controlled by the application and is used by the application to move the user through the virtual environment. The eye is often out of the control of the application (e.g. a user physically walking around) but may be tracked (e.g. head-tracker, motion platform) so the information is available. In order to know precisely where the user is in the virtual world, you need to know both the origin and the eye.

Walls in the physical environment have fixed locations either with respect to the physical environment - meaning that their virtual location is relative to the origin - or with respect to the user - meaning that their virtual location is relative to the eye. For example, a projection screen mounted on the wall would be considered to be defined relative to the origin - as the eye moves, the screen does not. However, a head-mounted display would be defined relative to the eye, as it moves with the user.

A frame (short for "frame of reference) defines a relation between two spaces. It is defined as a set of three vectors: